While employability per se looks set to remain a contested topic, it is evident that it is typically well established in the lexicon of HE providers – with attention now coming to bear on graduate outcomes at a disciplinary level there is an ever-increasing scrutiny around graduate earnings, progression and the ‘inequalities’ of various subjects as highlighted in various media articles such as; ‘The degrees that make you rich... and the ones that don't’ BBC (2017). This ‘value for money’ narrative often has a negative impact and sells the sector short as it undermines the wider value of higher education – yet arguably it has also created a greater focus on enhancing employability across a plethora of subjects.

While employability skills are never far removed from the debate, the research is clear; employability in itself is far more complex than proponents of ‘employability skills’ suggest[1]. However, those championing employability are often caught externally within varying debates around the use of language and terminology – typically coupled with the ‘skills gap’ paradigm - which is perhaps best highlighted by universities now ‘hitting out’ against the dangerousness of the ‘skills obsession’ THE (2019).

Starting with the premise that HEIs typically do a good job – there are challenges; consistency of provision, inclusivity of opportunity, labour market detail and socio-geographic factors to name but a few, but HEIs have, in general, risen to the challenge of enhancing employability. Knowledge Transfer initiatives, Innovate UK work, university incubators, entrepreneurship programmes and a plethora of industry/academic partnerships create both jobs and the necessary components of employability that are intrinsically linked to such activities.

To really make a difference and change the narrative, we must move the debate beyond semantic arguments and provide a renewed focus, positioned around three propositions:

- Clear purpose, leadership and implementation of employability outcomes clearly linked to strategic aims.

- The ability to collaborate and transfer knowledge to ensure we are designing inclusive employability opportunities for all students.

- A better, sector-wide articulation of the value that higher education creates in relation to employability.

We are all aware of the varying external factors that can influence graduate employment rates – and with higher level employment remaining fairly static over a number of years it may be pertinent to ask what HEIs are doing. However, these static measures of employment do not measure or articulate the value that universities contribute to employability.

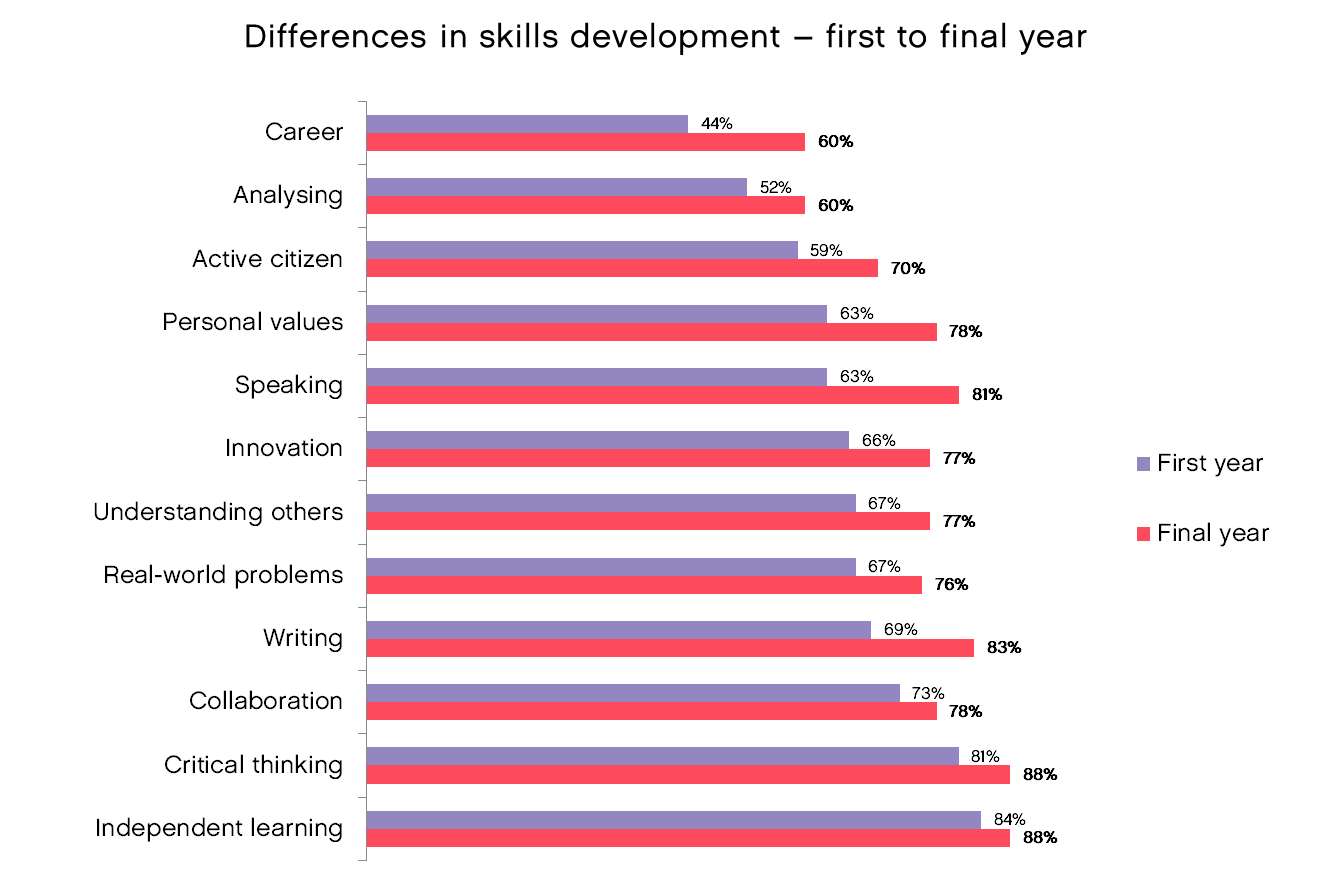

Perhaps the best evidence to support the work HEIs have put into employability comes from UK Engagement Survey data – the graph below shows that from first year to final year reporting student awareness and perception of skills show a marked improvement:

While taking the UKES data as a positive, there is arguably room for improvement too. So going back to the three propositions, what could this data look like with a clear(er) strategic plan and proper implementation aligned to this? What if all opportunities were as accessible as could be, with any variations suitable, robust and relevant? What story would the sector narrative demonstrate about higher education’s role in employability?

It’s accepted that employability is, at times, contentious, and consensus is not being sought here in terms of a definition or use of language regarding ‘skills’. Yet, if we are to pause and think about what students want from Higher Education, we are fairly assured that is not just the qualification, nor is it necessarily about ‘that first job’ – it may be the job after that and the job after that, or multiple careers, or individual ventures and aspirationally about making a difference – all of which speak volumes to the need to develop employability alongside subject knowledge and technical skills.

Join us for an exploration of this topic in the joint tweet chat on Wednesday 27th February at 20:00 GMT. #AdvanceHE_Chat #LTHEchat

[1] for example see Yorke & Knight (2004), Dacre Pool and Sewell (2007) Bennet, Richardson and Mackinnon (2016), Tomlinson (2017)

References:

Bennett, D., Richardson. S., and MacKinnon, P., (2016). Enacting strategies for graduate employability: How universities can best support students to develop generic skill Part A. Canberra, ACT: Australian Government, Office for Learning and Teaching, Department of Education and Training.

Dacre Pool, L & Sewell, P 2007, 'The key to employability: developing a practical model of graduate employability' Education and Training, vol. 49, no. 4, pp. 227-289.

Tomlinson, M. (2017) ‘Forms of graduate capital and their relationship to graduate employability’, Education + Training, Vol. 59 Issue: 4, pp.338-352

Yorke, M. and Knight, P.T. (2004), ‘Embedding Employability into the Curriculum’, Higher Education Academy, York.