"I know who I am, but who am I really?” This is a direct quote from a participant on an Advance HE senior leadership programme. Now, our programmes are not designed to inspire an identity crisis in those participating, but to create a safe, forgiving space within which to be open to new insights and realisations regarding leadership identity.

You may think that people will judge you by results, that the end justifies the means, but you would be mistaken. People will ‘remember’ you by results - but in terms of leadership, they will judge you by your character and credibility. People will judge you more than anything else on the quality of relationship they experience. Even in the most high-stakes environments ‘being’ is at least as important as ‘doing’. And if you wish to engage a highly diverse community of scholars and professionals in a university context, then in terms of leadership identity, how you are with people, the trust you inspire and the respect you show will matter every bit as much as anything you achieve. Enabling the community is, perhaps, the primary goal.

Leadership identity is far more than a public relations exercise. Certainly, though, the more senior leaders become the more they may feel that they are having to manage some kind of leadership brand. Alarm bells should ring at the very notion! This is a recipe for remote leadership, driven by image and impression rather than by integrity. Minions start to carry messages, dry written monthly updates become the primary contact point, and ‘my inbox is always open’ becomes the proxy for approachability. There is something naturally inverse about great leadership. The higher you go the more humble you need to become.

The origins of leadership identity

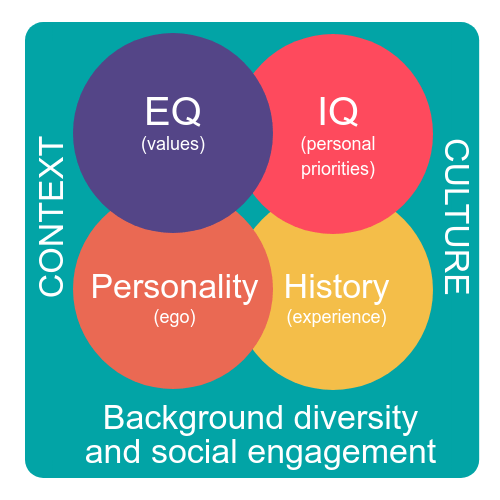

"So, who am I and what sort of leader am I going to be?" As a model to help conceptualise the origins of leadership identity, the figure shown above is a strong starting point. Each of the headings in the model could be a long essay or thesis in its own right, but below is a summary of the key elements which combine to create your unique leadership identity:

EQ – Emotional Intelligence

The foundation of emotional intelligence is self-awareness[i]. “You can’t be true to others until you are true to yourself.”[ii] And creating energy and engagement around purpose has to begin for leaders with a strong sense of self. This will involve our personal history and critical incidents in our lives, it will involve a personal hierarchy of values and how we can live and express them in our work, and it will involve an intellectual appreciation of our personal goals and priorities. No leader is an island, and the identity of the leader is mediated through each and every point of contact with others. ‘Who we are’, the social identity of the group, is as important as ‘who I am’. As groups mature and organisations or projects progress, the identity of the leader, or the character of shared leadership, will become more and more intertwined with the cultural dimensions of the social group. To put this another way, the story of the leader will become part of the unfolding narrative of the team or organisation. For leaders to be open to this requires both poise and courage. And the greatest barrier to this is ego, where our own sense of self-importance matters more than the collective story of the group.

IQ – Intelligence

Universities are full of very intelligent people. They are bright, smart, driven and very critically-attuned. Being smart is a very important part of their identity, and a leader’s knowledge, intellect, technical competency and experience will be a significant element of who they are. This can, however, be manifested in different ways and with different levels of emphasis. For example, to always be the smartest person in the room is a big ask for leadership, in any context. If we are not careful we can also get caught up with the badges of intellect – recognition, prestige and eminence – and see these as a proxy for leadership. Intellectual leadership, an incredibly important aspect of the academic endeavour, is not the same as team or organisational leadership, although it may be significant in terms of the individual identity of the leader. Another aspect of intelligence can be seen in the highly refined cognitive skills needed for critical appreciation and problem-solving. This ability to comprehend and analyse and to be intellectually attuned to the purpose and position of the team or organisation is part of the identity of the leader. It also links with the intellectual reasoning that sits behind our rational understanding of our personal priorities or ‘life goals’, as they are sometimes termed.

Personality

If you have ever experienced, for example, being a ‘slow’ person in a ‘fast’ organisation you will know the role that personality plays in our working lives. And this does not mean intellectually slow, or slow to grasp things - far from it. It means, essentially, the quality of introversion where the need to deliberate, ponder, think, and have time and space alone to reflect, is a core part of the person’s default operating system, or personality. Introversion, used as an example here, is just one dimension of personality type. Personality is essentially about how we see the world, how we make decisions and how we like to live our lives, and this is a very deep and genuine aspect of human diversity. Our ego is caught up in this, how we measure ourselves and our success, and self-awareness around personality is a very important gateway to developing and refining leadership identity. It is also a platform for more harmonious and inclusive communication. To know that not everyone is like you, to really respect difference, and to have empathy and compassion for others, is perhaps the cornerstone of a firmly based leadership identity.

History

Everyone has a history. Like it or not, it is inescapable. And all leaders have a history. Moving to a new role or to a new organisation can sometimes be an opportunity for a bit of personal reinvention, but who we are will always catch up with us. There are a hundred-thousand moments that made us who we are and this... this is just the next moment. And so, reflecting on all of those moments and experiences out of which our leadership identity is born is an important part of leadership development. Constructing a personal timeline and looking at the highs and the lows, the critical incidents, the influential others, the turning points and the key decisions is a powerful way of understanding who we are. It is also a perspective that can help us more profoundly relate to others.

Our personal history is also what enables us to have character and courage, particularly during more difficult times. Times, perhaps, when we become ‘the monster’ as this extract from Jocelyn Davis powerfully illustrates:

The backbone of leadership character is courage, and courage is tested whenever we face a ‘monster’: something we’ve put into motion that is turning out badly and threatening our reputation. But once or twice in our lives as leaders, we’ll encounter an even bigger test. We’ll overhear a trusted friend or colleague talking about us as if we were the monster. We will hear fear, anger or (worst of all) contempt in his or her voice. What we do next reveals our character as nothing else can.”[iii]

Context, culture, background diversity and social engagement

Surrounding all of these individual factors are the social environment and culture within which the leader leads. Whether a leader by title and position, or a leader through influence and the needs of the moment, the social environment and the narrative of the group will have a great deal of bearing upon the identity of the leader in action. For some the very notion of being a leader as part of their overall identity may not, initially at least, sit very comfortably. The wonderfully titled article by Martin Parker (2004[iv] )

Becoming Manager: Or, The Werewolf Looks Anxiously in the Mirror, Checking for Unusual Facial Hair”, captures this tension perfectly. So, the social or community aspect of how leadership is constructed, through command or consent, particularly in an environment like a university, will be critical. It brings in the key question how identifiable does leadership need to be and can it, at times at least, be shared and distributed in an inclusive way?

In football and some other team sports the identity of the leader is shown by the wearing of an armband. The person chosen to be captain may be an outstanding leader, armband or not, but sometimes the appointment may seem a little arbitrary and without the armband to denote leadership the role might be unclear. And when through tactics or injury the captain is substituted the armband is passed in an instant to another player. There has to be a leader, even if only as a reference point for the officials. But is this leadership or is this captaincy actually a kind of ‘headship’? To continue the football theme, another way of seeing the world is that everyone on the pitch is a leader. A leader in their area, a leader in their role, a leader when the flow of the game comes their way, a stoic leader when the tactics of the game call for defence, a flamboyant leader, perhaps, when the tactics of the game call for attack. We don’t defer to the person with the armband, we allow leadership to be shared and flow to the point of need. This is truly distributed leadership, where the identity of the leader is not fixed but is socially constructed within the shared endeavour of the collective.

Identity in action

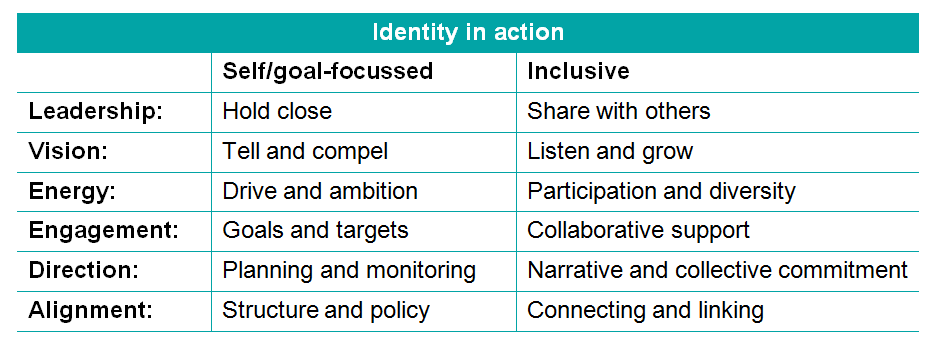

Leadership identity is formed in action – it is both what we do and how we do it – and this can be expressed in very different ways. Our leadership identity can be self/goal-focussed or it can be inclusive, and this can vary at different times and in different situations. To illustrate this, the art of leadership can be captured by the model VEEDA – vision, energy, engagement, direction and alignment[v]. Using this simple model, the table below contrasts in broad terms a leadership identity which is self/goal focussed with an identity which is inclusive:

So, who are you? Or rather, who do you think you are? And when it comes to your leadership identity in action, does how you see yourself match reasonably the identity experienced by others. Is there congruence? Are you authentic? And are you receptive to the kind of feedback that would help you to calibrate your self-perception with the experiences of those around you, near and far? This is crucial for ongoing leadership development.

Conclusion

There is an expression that ‘people join organisations but leave managers’. Undoubtedly there is a lot of truth in this. It could also be said that ‘people follow leaders but drift away from leaders with no self-awareness’. Attuned leadership is responsive to the needs of others, and it is in that fine, carefully balanced responsiveness that true leadership influence is made. An influence based on identity.

Experiential leadership development programmes such as Advance HE’s highly regarded Preparing for Senior Strategic Leadership crucially provide time, space, support and friendship to explore, discuss, refine and develop leadership identity. This quality of reflective space is a rarity in our modern world. As the Swedish physicist Bodil Jönsson[vi] put it:

Concentrated, inspired conversation is a widely undervalued source of new knowledge, new feelings, new impulses.”

[i] Goleman, D. (1996) What Makes a Leader? Harvard Business Review, USA, June 1996.

[ii] Parkin, D. (2017). Leading Learning and Teaching in Higher Education: the key guide to designing and delivering courses. Routledge: Oxon and New York.

[iii] Davis, J. (2016). The Greats on Leadership: Classic Wisdom for Modern Managers. Nicholas Brealey: Boston.

[iv] Parker, M, (2004). Becoming Manager: Or, The Werewolf Looks Anxiously in the Mirror, Checking for Unusual Facial Hair. Management Learning, vol 35., pp. 45-59.

[v] Parkin, D. (2017). Leading Learning and Teaching in Higher Education: the key guide to designing and delivering courses. Routledge: Oxon and New York.

[vi] Jönsson, B. (2001). Unwinding the Clock: Ten Thoughts on Our Relationship to Time. Harcourt: San Diego.

Doug Parkin is Principal Adviser for Leadership and Management at Advance HE. He co-facilitates the Preparing for Senior Strategic Leadership programme.

Find out more about Advance HE's Preparing for Senior Strategic Leadership Programme