Sarah Hubbard and Barbara Bassa from Advance HE share details of Organisational Resilience = Leadership Well-being? Creating healthy eco systems in HE from inside out, a new Advance HE Member Benefit which aims to explore the emerging needs of leadership resilience and well-being in the HE context.

From regular discussions and deeper consultative conversations with Advance HE members over the last six months, we gathered a long list of challenges faced by the post-pandemic higher education (HE) sector: a stricter and more rigid regulatory environment, scarce funding sources, the cost of living crisis; changes in student behaviour and engagement, deteriorating wellbeing of students and staff, increasing number of deaths by suicide, burnout, stress and retention problems, to name a few. The picture is quite overwhelming.

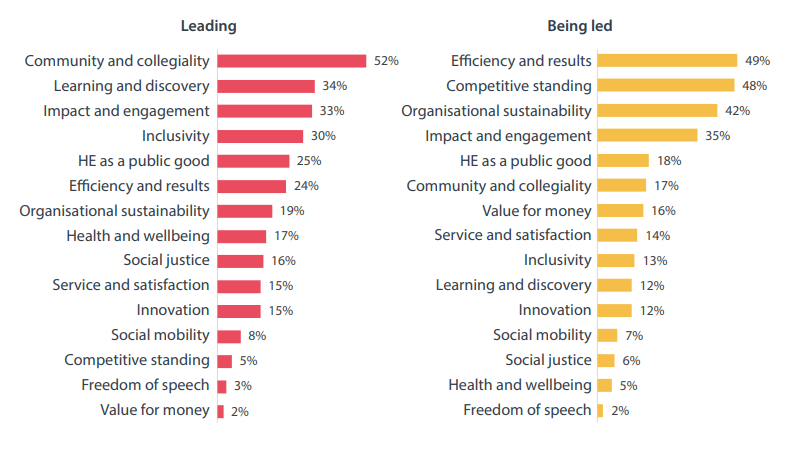

Advance HE’s Leadership in Higher Education Survey Report offers an additional lens to understand the experience of these increasing pressures. Respondents were asked to reflect on their experiences as a leader compared to their experiences of being led within their organisations. What emerged was a significant contrast in the values experienced between these two dimensions. What is expected to be done and delivered appears to be misaligned to individual purpose, values and aspirations (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Most important values linked to purpose (Neves J. & Parkin D., 2023, p.23).

In the prioritisation of focus, the experience of being led (what is expected from leaders by their organisation) is more concerned with efficiency (49%) and competitive standing (48%) with key areas like inclusivity (13%) and wellbeing (5%) being positioned towards the bottom of the list. These priorities seem to be opposing the real challenges and priorities around wellbeing, collaboration and inclusion, consistently expressed by respondents.

This is almost certainly linked with the “range of competing expectations and demands on HEIs and the leaders, managers and other professionals working within them” (Watermeyer et al, 2022, 26). Holding this tension is further challenged around the respondents’ experience of feeling valued. Less than half of them feel their unique background and identity is valued (strongly agreed (22%), mostly agree (26%)); and only 1 in 3 respondents (33%), said that their leadership role and contribution was very much valued (somewhat valued (43%), not very valued (18%), not at all valued (5%)).

The prioritisation of developing a positive and enabling culture was a high priority for professional services leaders (53%) and strategic level academics (49%) and lower for academics (33%) and mid-levels academics (29%). This can be appreciated with curiosity and caution. As pointed out by an organisational culture expert, Edgar Schein, where a culture is not managed, it manages the individual and that might be out of awareness. He goes further to argue that the most important role of leadership is to manage the culture (Schein, 2004).

(Un)-intentional design

The picture emerging from the survey would suggest that HE leaders are currently more preoccupied with the ‘what’ (task), as opposed to the ‘why’ and the ‘how’ (culture). This sits contrary to the vocational nature of higher education which attracts colleagues with a strong desire to make a difference in the world. Managing this values conflict often comes at a personal cost.

Especially, when experiencing pressure, individuals, teams and (by extension) organisations can be drawn into black and white thinking of ‘this or that’, ‘competitive standing or wellbeing’ as opposed to considering the dynamic interplay of ‘both’. In HE, binary thinking is very much baked into our organisational design eg professional services or academic colleagues, staff or students, Arts or Sciences, Research or Teaching and the list could go on. Operating in this way, colleagues may be tempted to discount or ‘other’ and in turn, it can create unhelpful patterns in decision making (eg no action or imposed action), siloing or duplication in service design (eg staff wellbeing or student wellbeing).

Frame of reference

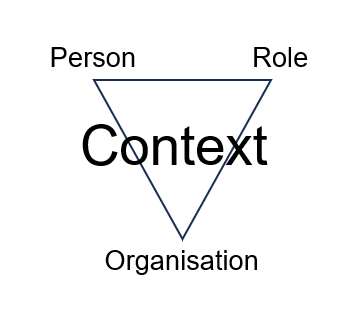

So far, we have explored the context, the experience of the role and aspects of organisational design in organisational wellbeing. It is also important to account for the person/people dimension, the role that we play in our organisations (see Figure 2). We need to recognise that we bring ourselves (or our-beings) to work too, and the work is a dynamic exchange between complex beings.

Figure 2: PRO Model, de Graaf & Kunst, 2010

The articulation of ‘wellbeing’ rarely conjures a shared frame of reference. Is it doing yoga? Is it an employee assistance programme? Is it physical, emotional or spiritual? Is it a fad? It can be a word that is thrown around inconsequentially and often disregarded.

What has got lost along the way, is the hyphen in ‘wellbeing’. When we include the hyphen, we are led to a deeper meaning and connection and the etymology of ‘Well’ and ‘Being’; “the state of being comfortable, healthy, or happy” (Oxford English Dictionary).

Also disconnected, is that well-being leads to well-thinking and well-doing – the precise capabilities that we need to enable our students, lead groundbreaking research and respond effectively to the challenging context we are experiencing. Good health and well-being is the 3rd of the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals, following no poverty (1), zero hunger (2) and before quality education (4); “ensuring healthy lives and promoting well-being at all ages is essential to sustainable development” (UN.org).

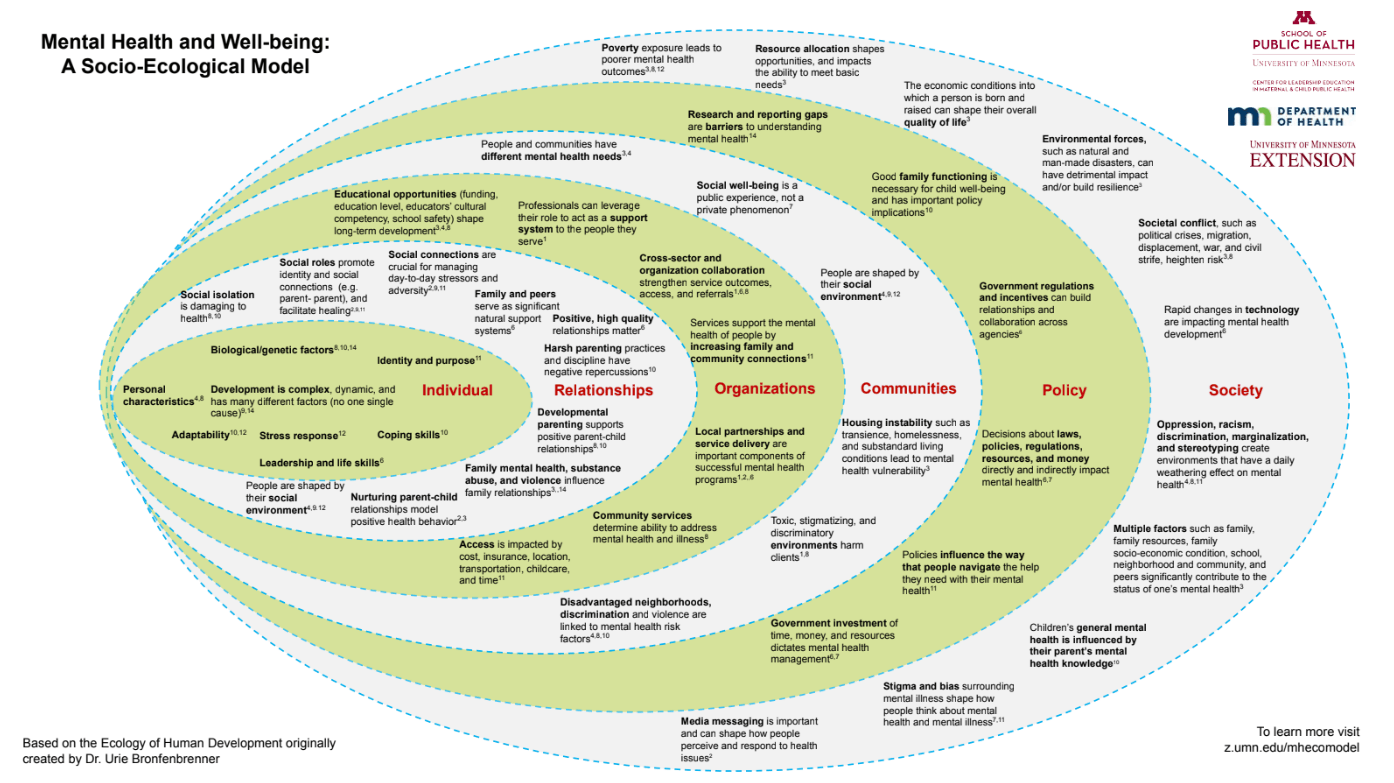

If we use the lens of a socio-ecological model of mental health and well-being (See Figure 3), we can begin to understand that the long list of challenges identified in the consultations with the sector reflects the multi-dimensionality of well-being. It recognises the interconnectivity between individual, relationships, organisations, communities, policy and society as the whole.

Figure 3: Mental health and well-being: A socio-ecological model (University of Minnesota, 2021)

Invitation

We invite you to explore these and some other questions during our workshop - Organisational Resilience = Leadership Well-being? Creating healthy eco systems in HE from inside out - on Monday 17 July.

References

De Graaf, A. & Kunst, K. (2010) Your leadership role and professional identity. Sherwood Publishing. Hertford.

Neves J. & Parkin D. (2023) Advance HE Leadership Survey for Higher Education. York: Advance HE. Available at: https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/membership/leadership-survey-and-framework#survey [accessed June 23]

Oxford English Dictionary. Available at: https://www.oed.com/oed2/00282689 [Accessed June 2023]

Schein, E. (2004) Organizational culture and leadership (3rd ed.). Jossey-Bass. San Francisco.

United Nations Sustainable Development Goals. Available at: https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/health/ [Accessed June 23]

University of Minnesota (2021) Mental health and well-being: A socio-ecological model Available at: z.umn.edu/mhecomodel [accessed June 23]

Watermeyer, R, Bolden, R, Knight, C and Holm, J (2022) Leadership in global higher education: findings from a scoping study. York: Advance HE. Available at: www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/leadership-globalhigher-education-findings-scoping-study [accessed March 2023].

Organisational Resilience = Leadership Well-being? Creating healthy eco systems in HE from inside out

Find out more about the project and register to participate in the workshop on Monday 17 July.